Rabelais publishes two ethics papers for nurses

body copy Heading link

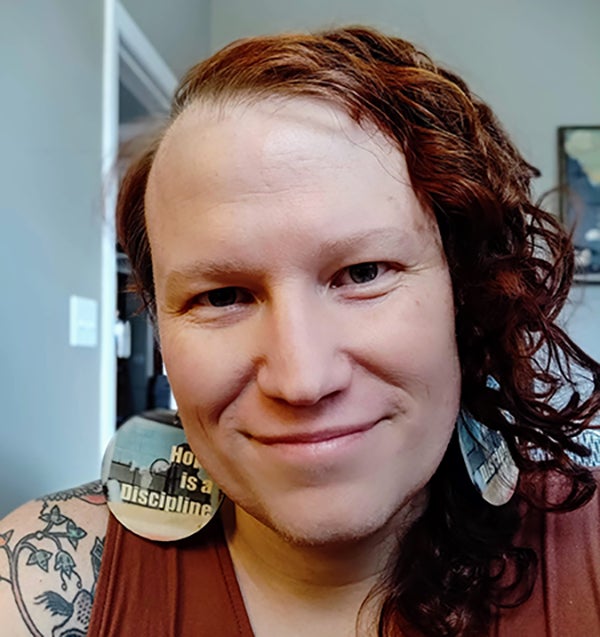

Assistant professor Em Rabelais, PhD, MBE, MS, MA, RN (they/themme) is the author or co-author of two ethics papers published in peer-reviewed journals in December 2020.

In the first paper, in the Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, “Missing ethical discussions in gender care for transgender and non‐binary people: Secondary sex characteristics,” Rabelais establishes a starting place for clinicians to direct their attention on “how to shape their action-oriented responses in the care of secondary sex characteristics for trans [and non-binary] individuals.” Rabelais’s emphasis in this paper is critical of current gender care for trans feminine people, who are subjected to violence at higher rates than any other group in the United States.

They shift ethical focus from normative (e.g., principle-based) to narrative ethics to “center patients in the clinical story, require that we [clinicians] believe our patients and communities whether we understand them or not,” says Rabelais, adding that disrupting biomedicine’s cisgender bias makes it possible for clinicians to see how cisgender standards of medical necessity and “cosmetics” are transmisic (misic refers to hate). The outcomes make it possible for trans and non-binary people to gain access to gender care that ranges from addressing dysphoria to preventing verbal, emotional, sexual and physical violence, including death.

Rabelais provides practical steps for clinicians, especially when they do not understand trans existence: “believe trans [and non-binary] people’s statements, responses, and narratives; reflect on the discrepancies between clinicians’ sociocultural learning and the sociopolitical existence of trans lives; and then to act only after listening, believing, trusting, and reflecting.”

A second paper, published by The Journal of Clinical Nursing, is entitled, “Ethics, health disparities, and discourses in oncology nursing’s research: If we know the problems, why are we asking the wrong questions?” In it, Rabelais and co-author Rachel Walker, PhD, RN, FAAN (they/them), take on questions about the influences that have shaped discussion of health disparities in oncology nursing, and nursing writ large, and how assumptions about health and power are woven into health disparities discourse.

The authors establish their ethical starting place from and within “critical sociopolitical theories such as radical queer Black feminism, disability justice, trans liberation, reproductive justice, design justice, Indigenization, abolition, and community care,” they write, in order to critique not only the Oncology Nursing Society’s (ONS) Research Agenda, but also “how the nursing profession defines what is ‘normal’ and appropriate in its practice, education, research, and other interactions.”

Rabelais and Walker deliver several practical steps for nurses. Among others these include: believing patients and community research partners by making it important that nurses “read, listen, reflect, and repeat, all while believing the written, recorded, or spoken empirical realities of patients, families, and communities,” they write. Importantly when these entities “name us or our institutions as oppressors, we must accept that naming,” whether that naming is that we are being racist, ableist, transmisic, or otherwise oppressive. The authors assert that nurses’ and nursing’s responsibilities are to do the work to understand this naming; it is not the responsibility of those being oppressed to undo the oppression of the oppressor.

Rabelais and Walker state that we remain left with several questions, rather than answers. Among these are the following questions and process, “‘Who might this harm?’ Answer then revise: ‘Who might this harm now?’ Answer then revise: ‘Are these harms worth the activity?’ And repeat this process,” while concluding that “Nursing’s white demographic holds our power. We (authors) are white, and we think it’s well past time to cede this power.”